Feature Image: Women’s Information Network (WIN). (2023) Postcard – Women Fight for Access, Freedom, Choice, Digital Repository of Ireland [Distributor], Digital Repository of Ireland [Depositing Institution], https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.rf56c215x. Rights: Copyright Women’s Information Network. Licensed for reuse CC BY 4.0.

Guest blog by Cara Brophy-Browne and Susan Birmingham

Back rooms in old Dublin pubs, empty lecture halls, hotel lobbies, and museum cafes; these are the impromptu recording locations we found ourselves in in the early months of 2016. It was in these spaces that six women were interviewed for the very first time about their participation in an underground abortion access collective that functioned in Ireland in the 1980s and 1990s. Women who had spent years of their lives providing support and information to women seeking abortions, during a time when it was illegal to do so. Due to the secretive nature of their work, our interviewees had never before spoken publicly about their time in the collective.

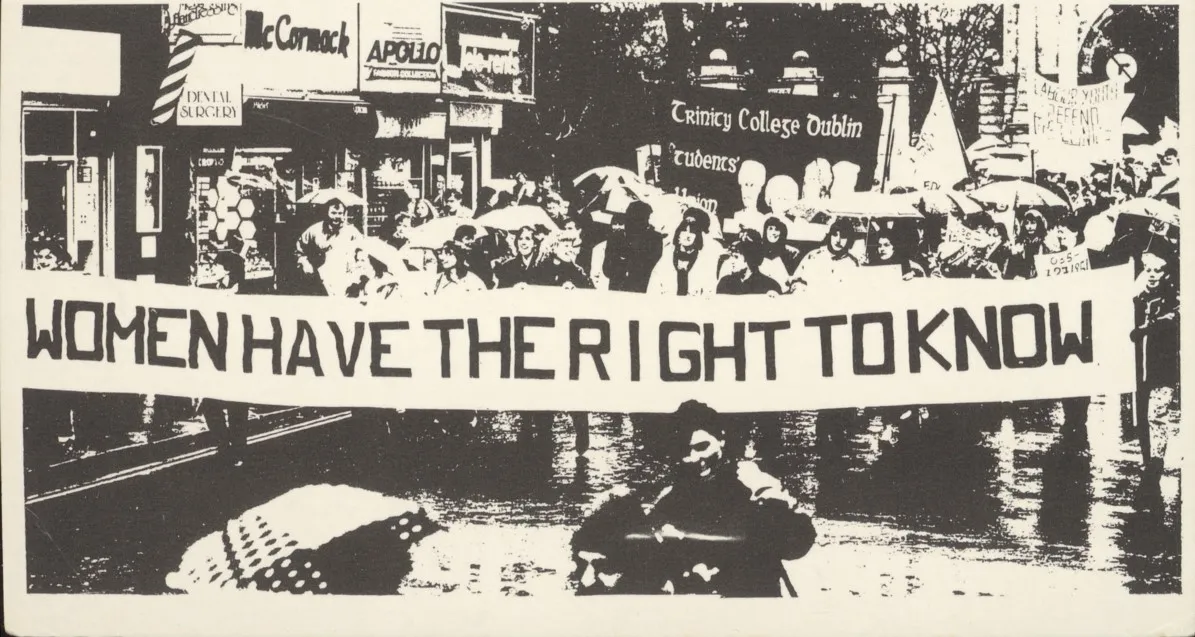

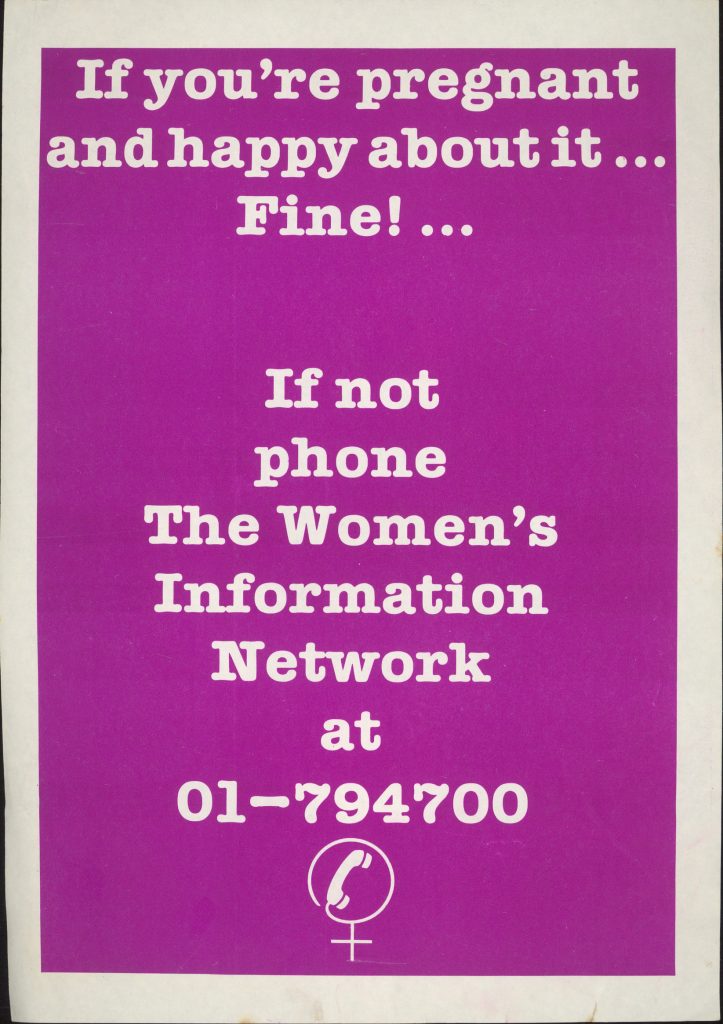

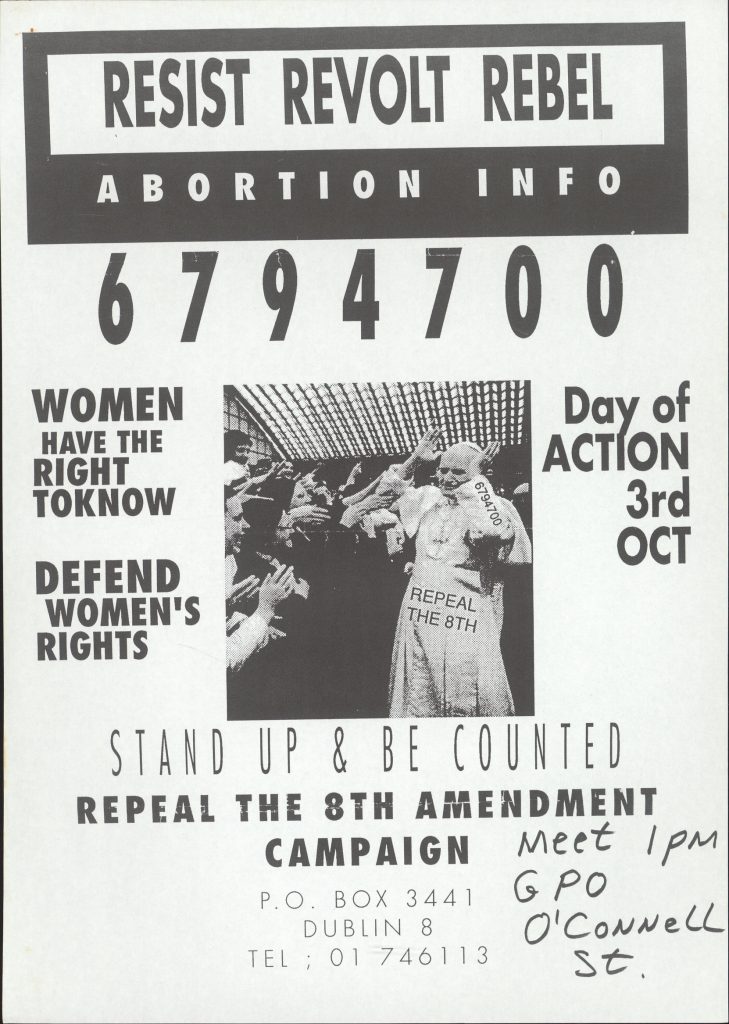

Women’s Information Network (WIN) was a non-directive abortion information service active from 1987 to 1996. WIN ran a phone line from, according to the interviewees, a tiny cupboard-like room under the stairs in the Dublin Resource Centre on Crow St. in Dublin. The phone number was disseminated using stickers, written on toilet doors, and chanted at marches. These persistent women, whose archive and interviews are now available in the Digital Repository of Ireland (DRI), manned that phone line four days a week for close to a decade, sitting alone or in pairs in the tiny room waiting for a woman in need to call. When a woman did call, which they did in their thousands, WIN was able to provide the information necessary to make an informed decision regarding an unwanted pregnancy – as well as vital information on how to travel to England to procure a safe abortion.

In their interviews, the WIN women proudly emphasise the practical nature of their work; they were truly a timely and pragmatic response to the particular barriers to reproductive freedom facing women in Ireland at the time. The specific barriers WIN were attempting to overcome existed at the intersection of Ireland’s policies of control over women’s bodies and Ireland’s historic culture of censorship. The infamous 1929 Censorship of Publications Act prohibited the publication of ‘unwholesome literature’, including a publication that ‘advocates the unnatural prevention of conception or the procurement of abortion or miscarriage […]’.[1] In 1979, the Health (Family Planning) Act, which legalised condoms and contraceptive pills in certain circumstances, amended the the Censorship of Publications Act 1929 so as to continue to regulate the publication or display of written material ‘which might reasonably be supposed to advocate the procurement of abortion or miscarriage’, continuing the ban on abortion information literature.[2] While the 1983 Referendum on the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution is familiar to many, a further blow to abortion information access came with the Hamilton Judgement in 1987. The Hamilton Judgment granted the Society for the Protection of the Unborn Child (SPUC) an injunction against Dublin Well Woman Centre and Open Line counselling, restraining them from giving non-directive pregnancy counselling. Following this judgement there was no legal clinic where a pregnant woman could receive advice or information regarding all of her options. In March 1988, the Irish Supreme Court, confirming a High Court judgement, ruled that it was illegal to provide information about clinics abroad that were willing to carry out abortions’.[3] Understanding what this would mean for women WIN, during and in response to this moment of extreme censorship on abortion access information, established their phone line.

In these interviews, the women of WIN give their first-hand accounts of this period of censorship and their motivations for forming the network. As one woman remembers, numbers for and information about clinics in the UK were physically cut out of British magazines when they arrived in Ireland: ‘They used to have to take out the Marie Stokes ads. I mean it was just ridiculous what they expected international companies to do… and what they did do. The number when they came over to Ireland would be blanked out’. She goes on to recall how ‘books were supposed to be taken out of the library’.[4] This media censorship had a direct effect on WIN when in 1992, the Irish Times edited a photo of WIN at a rally to remove the phone number from the collective’s banner.

In the context of these censorship measures, WIN’s work was vital. As one woman notes, ‘it wasn’t even the best [thing], but it was the only thing’.[5] While the restrictions on abortion information left them vulnerable to legal action, the interviewees give their reasons for believing they would not be prosecuted, noting that even the state may have viewed them as a ‘necessary evil’.[6] Although no one was arrested for their involvement with WIN, many of the women mention an awareness that their work was known to the Guardaí.

Their ambiguous and uncertain legal position had other consequences for the collective – including discussions among members about who felt safe to represent the group in public. WIN’s illegal status also had an effect on their relationships with other women’s organisations. One WIN member noted, ‘there was kind of a real absence of support from women’s groups and the women’s movement in Ireland at the time’.[7] The women recall a fear of guilt-by-association that resulted in WIN’s ‘fringe status’ in the wider movement, creating a kind of second-censorship from within the movement itself. This may explain their absence from many of the recent narratives of the struggle for abortion rights on this island. At the time, and as you will hear throughout these interviews, WIN responded to their precarity by focusing on the material, immediate, and practical importance of their work in the service of Irish women. They fundraised, leafleted, marched, researched, visited clinics, recruited and organised rotas of volunteers, all in the service of keeping the phone line open four days a week – with record of support given to 1,495 Irish women from 1987–1991 alone.[8]

As young activists and artists ourselves, we wanted to understand and bring awareness to the hidden histories of this struggle, and were fortunate enough to sit down with these activists to discuss their memories and impressions of these events twenty years on. Their testimonies on their work and this period in Irish history are eye-opening, and their insights into the challenges ahead of the then contemporary Repeal the Eighth campaign can only be described as prophetic.

Cara Brophy-Browne and Susan Birmingham

These interviews were recorded in 2016 as part of our own research for a documentary theatre play, The WIN. At that time, women’s groups across Ireland were in the midst of another hard-fought campaign to secure a referendum on the Eighth Amendment. As young activists and artists ourselves, we wanted to understand and bring awareness to the hidden histories of this struggle, and were fortunate enough to sit down with these activists to discuss their memories and impressions of these events twenty years on. Their testimonies on their work and this period in Irish history are eye-opening, and their insights into the challenges ahead of the then contemporary Repeal the Eighth campaign can only be described as prophetic. Listening to these interviews or reading their transcripts in 2023 provides a rich and nuanced understanding of the particular position of women in Irish life, both historically and today.

[1] Irish Statute Book, Censorship of Publications Act 1929.

[2] Findlay, M. J. “Criminal liability for complicity in abortions committed outside Ireland.” Irish Jurist (1966-) 15, no. 1 (1980): 88-98.

[3] Lawson, Rick. “The Irish abortion cases: European limits to national sovereignty?.” European Journal of Health Law 1, no. 2 (1994): 169.

[4] Cara Brophy-Browne, & Susan Birmingham. (2023) WIN Activist: Patricia Prenderville, Digital Repository of Ireland [Distributor], Irish Qualitative Data Archive [Depositing Institution], https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.0574fk282.

[5] Cara Brophy-Browne, & Susan Birmingham. (2023) WIN Activist: Fiona Bergin, Digital Repository of Ireland [Distributor], Irish Qualitative Data Archive [Depositing Institution], https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.zp399619d.

[6] Cara Brophy-Browne, & Susan Birmingham. (2023) WIN Activist: Imelda Brophy, Digital Repository of Ireland [Distributor], Irish Qualitative Data Archive [Depositing Institution], https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.zw13bz87n.

[7] Cara Brophy-Browne, & Susan Birmingham. (2023) WIN Activist: Mary Gordon, Digital Repository of Ireland [Distributor], Irish Qualitative Data Archive [Depositing Institution], https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.xk81zc95q.

[8] WIN Archive 1992.

The Women’s Information Network Interviews collection was created by Cara Brophy-Browne and Susan Birmingham and deposited in the Digital Repository of Ireland by the Irish Qualitative Data Archive as part of the Wellcome-Trust funded Archiving Reproductive Health project.