In a new DRI blog, DRI Education and Outreach Manager Deborah Thorpe meets with DRI Digital Archivist Kevin Long, Killian Downing of Dublin City University, and Rebecca O’Neill of Wikimedia Community Ireland, to explore different perspectives on open licences and how the licences depositors select affect the use and reuse of digital content.

An increasing number of organisations, including libraries, galleries, and museums, are choosing to provide open access to their online collections, with fewer and fewer restrictions on how they are used. In 2020, for instance, the Smithsonian Museum released 2.8 million images of its collections into an open access platform. Before that, in 2018, Birmingham Museums Trust took the decision to make medium-resolution images of its out-of-copyright collections freely available with no restrictions. The Rijksmuseum states ‘our collection is for everyone. That’s why the Rijksmuseum makes its digitised collections and metadata available in the highest quality. And we don’t ask for anything in return’. The museum’s Research Services department is also building a digital infrastructure for sustainable Research Data management, inspired by the FAIR principles of findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability. Where copyright and database rights apply to digital reproductions and data, the Rijksmuseum waives these rights by using the Creative Commons Zero (CC0) Public Domain Statement.

So, what exactly is a licence? Digital Repository of Ireland (DRI) Digital Archivist Kevin Long explains that licences give ‘permission for use and reuse of copyrighted material – for specific purposes, people, territories or durations’. In DRI, information about which licence applies to digital material can be found in its metadata. Our Repository Walkthrough video explains how to find the metadata relating to the Archiving Reproductive Health materials in particular, including their licence.

There are many different licences to choose from, ranging from very restrictive to very open. If you, your organisation, or group, have chosen to maximise the contexts in which your material can be used, an open licence would be the most appropriate choice. The Smithsonian, for instance, encourages the public to ‘use, reuse and transform [its data and material] into just about anything they choose’. However, making this decision does present challenges, as well as opportunities. DRI actively promotes the opportunities that open licences present, and our team supports our members and communities to make informed decisions about which licence is appropriate for their collections.

With that in mind, in this interview, DRI Education and Outreach Manager Deborah Thorpe meets with DRI colleague Kevin Long who explains the practicalities and implications of selecting licences on DRI. Also joining the conversation is Killian Downing of Dublin City University, a DRI member that has chosen a very open licence for its digital materials. Finally, we are given important perspectives on the use and re-mixing of openly licensed materials by Rebecca O’Neill of Wikimedia Community Ireland.

Deborah Thorpe: Kevin, can you say a bit more about licensing and how it relates to copyright?

Kevin Long: Licences allow the copyright holder to set the conditions under which others can reuse their material. Everyone is familiar with the expression ‘all rights reserved’; licences are sometimes described as a way of setting ‘some rights reserved’. In the Repository, we use licences to alert the public about how different published objects and collections may be used. This is different to access, i.e. what the public can see and download when they browse the Repository. Access levels are set directly by the depositors. To licence an object you must be the copyright holder, or be acting on their behalf. Equally, you cannot apply a binding licence to an object that is out of copyright.

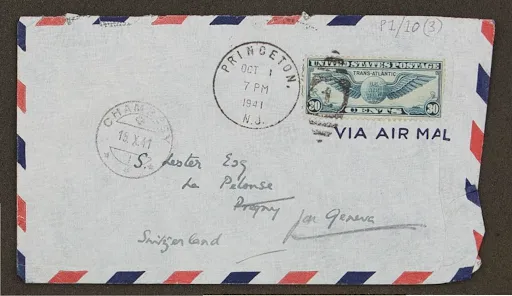

[Image: selection from Diary 10: April – December 1941: Lester, Seán, 1888-1959. (2021) Diary 10: April – December 1941, Digital Repository of Ireland [Distributor], Dublin City University [Depositing Institution], https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.4x51x802h. CC-BY-4.0]

Deborah: Who selects the licences for the digital material in DRI, and what kinds of licences are available?

Kevin: Licences are set directly by the depositors themselves – i.e. the organisations who own the collections and are members of the DRI. To publish a collection and set a licence, depositors must be the copyright holders themselves or be acting on behalf of the copyright holder. This is different from simply owning the physical collection and controlling who can access it on premises.

The DRI offers a variety of licences to choose from, including the full suite of Creative Commons (CC) and Open Data licences, an Open Covid Licence, public domain and Orphan Work declarations, and an All Rights Reserved declaration. Publishing an Orphan Work requires the depositor to first register the object on the Orphan Works database. An object set as All Rights Reserved is technically not licensed for reuse at all and the end user should contact the depositor to ascertain the conditions for reuse.

The DRI also has the option of an Educational Use Statement. There is no framework for educational licences in Irish law, so strictly speaking this is still an All Rights Reserved statement. However, when selected it will display a declaration that the objects are free for use within an educational context. Beyond this, the user must still contact the depositor.

Deborah: Killian, Dublin City University (DCU) decided to ingest the Seán Lester Collection under a very open CC-BY-4.0 licence. Can you tell me why you made that decision?

Killian Downing: Openly licensing our collections, whenever possible, is an imperative step in sharing our unique collections with international research audiences. We openly licensed the Seán Lester Collection in-line with our collection development policy and DCU Library Strategy. This CC-BY-4.0 licence is approved for cultural works and means anyone can freely access, use, modify, credit, and share for any purpose. The licence also supports our long-term cooperation and aggregation to the Digital Repository of Ireland and Europeana, where cultural heritage institutions are encouraged to share their digital collections with a specific licence or rights statement from the Europeana Licensing Framework. International frameworks and standardisation help support cultural heritage institutions with consistency and clarity in the complex landscape of copyright, licensing, and terms of use.

Deborah: What sources of information did you look at when deciding how to share the DCU collections?

Killian: It was important for us to better understand how cultural heritage institutions, both in Ireland and internationally, are working to openly licence their collections. The global Open GLAM survey, for example, collates and advocates how GLAMs (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums) and many other cultural heritage institutions are making their digital collections and metadata available openly for reuse. The survey has an extensive range of data points including institution name, type, and country, licences/rights statements for digital surrogates and metadata with links to terms of use and copyright policies. The survey is publicly available and we would recommend anyone with relevant open access data and/or policy to get involved and participate. If anyone has questions on licensing digital cultural heritage, we would also recommend joining the Europeana Copyright Community, which has relevant tools, resources, news, and guidance on better practice across the cultural heritage sector.

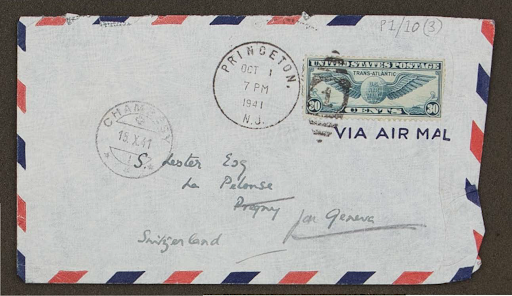

[Image: Global instances of Open GLAM, March 2022. Source: https://w.wiki/4u32]

Deborah: Rebecca, you are an advocate for open licensed images as the Project Manager for Wikimedia Community Ireland – can you speak to the power of open licences?

Rebecca O’Neill: When most people think about Wikipedia they think of the written content, and given that it is the largest encyclopaedia ever written, that makes a lot of sense. Increasingly, however, the community and users have come to realise the importance of media – in particular high-quality photographs, illustrations, sound files, and videos. As Wikimedians, we know that an image will make a reader of a Wikipedia article stay longer on a page. We have also come to realise the significance of photographs and other imagery when it comes to representation. We know that just under 20% of all the biographies on English language Wikipedia are about women, but we also know that they are less likely to have an image than their male counterparts. Bridging the gender and other representational gaps is a huge task we cannot accomplish in isolation, and many initiatives are working on this, from Art+Feminism to VisibleWikiWomen.

[Line up of some women welders including the women’s welding champion of Ingalls [Shipbuilding Corp., Pascagoula, MS], Image was uploaded as part of the #VisibleWikiWomen campaign]

This gap in representation is also cultural. When institutions in the US, UK, and Australia make their collections open, those higher-quality images make their way into Wikimedia projects and onto Wikipedia. This can have wider implications in contexts such as a postcolonial one, as we find in Ireland, and it raises numerous questions about who is being represented visually, how, and by whom. For the Irish context, it can cut both ways – opening up collections can mean that images and narratives of and from Ireland are better represented on projects such as Wikipedia, but secondly, we must also consider the implications for other people represented in the material culture held in Ireland and the responsibility to ensure the increased accessibility and use of any digitised objects openly. It is important to note that choosing more restrictive CC licences, such as non-derivative (ND) or non-commercial (NC), means they can not be used on Wikipedia and Wikimedia projects as well as other open knowledge projects.

Deborah: Kevin, if I could come back to you – do you have any advice for data owners in navigating the world of licensing, and selecting a licence for their digital materials? The Birmingham Museums Trust decided, for instance, to only make medium-resolution images available fully open access. Does DRI offer anything like this?

Kevin: The DRI offers different levels of access to the material – both in terms of which end users can access the material and the form they can find it in. Access can be set openly to the public, or limited to either logged-in users of the Repository or restricted only to bona fide researchers who must apply directly to the depositor. The last option is not recommended as a way to manage access to copyrighted material but rather to ensure legitimate use of potentially sensitive qualitative data sets.

Depositors can also set whether users can access the full resolution – or full quality versions of the preserved materials – or a system-generated surrogate which is typically of a lower than original quality but still sufficient for browsing and research use.

The DRI recommends that all our members select the most open licence possible to facilitate wider reuse and reach of their collections. While we recognise there is sometimes a lingering reluctance to use open licences, in practice the main advantage is that your collections actually get seen and reused. Placing restrictions can mean fielding a lot of inquiries for use that you might grant anyway, and will also turn users away because they do not want the hassle. In the end, a more open approach to licensing brings greater reuse of the collections and raises the profile of the organisations that hold them.

Deborah: Thank you for your time; it has been a pleasure to learn from the insight and experience that you are all able to offer!

The role that DRI plays in relation to the material in the Repository is in data stewardship – we preserve, manage, and provide sustained access to this social and cultural content for the long-term future. As Kevin states above, the data in the Repository has a variety of data owners. These are the organisations that are responsible for the data and primarily comprise DRI’s members. DRI is not the data owner for the majority of the data in the Repository, and so does not decide upon licences for the data – that decision remains entirely up to the owners, and each owner has its own set of objectives and concerns.

The responses given by both Killian and Rebecca make it clear that using a more open licence allows data to be shared and reused more widely, such as in academic publications and on social media. Many institutions are finding that in the ‘digital age we live in’, restrictions on remixing and reusing material commercially are becoming ‘out of step’ and that it is possible to push for an even more open approach. Using a very open licence (such as a CC-BY-4.0 licence) makes new and innovative reuses and explorations of the data possible – it can open collections to audiences that might never even have been imagined. As Rebecca has demonstrated, open licensing can even impact the historical narratives that we read online in projects like Wikipedia. As a result of wider use of open licensing, better quality images make their way onto the Wikipedia pages that we are looking at, and the presence of these images on these pages helps to ensure that people stay and read them.

DCU Library will be publishing new CC-BY-4.0 collections in the coming months, including the release of the first phase of the Charles J. Haughey collection. If you have any questions or queries about the DCU collections, please contact specialcollections.archives@dcu.ie

The DRI team is happy to discuss and offer advice on rights and licensing in relation to the Repository, if you have any questions or comments, feel free to email dri@ria.ie