In this blog post, historian Mick O'Farrell provides a fascinating overview of the diary of Herbert G Fitzgerald, which contains a 'wonderfully observant' eyewitness account of life during the Easter Rising of 1916. Mick recently transcribed this diary and it is available to researchers for sustained access on the Repository.

In this blog post, historian Mick O'Farrell provides a fascinating overview of the diary of Herbert G Fitzgerald, which contains a 'wonderfully observant' eyewitness account of life during the Easter Rising of 1916. Mick recently transcribed this diary and it is available to researchers for sustained access on the Repository.

Reading someone’s diary will never not feel intrusive … but when it’s 105 years old, and it’s describing life during a major historical event, then you can at least justify your snooping in the name of research.

In 1916, 21-year-old Herbert G Fitz Gerald [sic] was Librarian of TCD’s College Historical Society. He was the only child of Gerald (a Justice of the Peace) and Frances Fitzgerald, living at 74 Grosvenor Road in Rathmines, Dublin 6. And when the Easter Rising of 1916 began on Monday 24 April, luckily for posterity Herbert realised very quickly that he was witnessing a significant historical event. He took a notebook and wrote:

H.G. Fitz Gerald

Diary of events in Ireland during the

Sinn Fein Insurrection

1916

The following was begun on

Tuesday April 25th 1916.

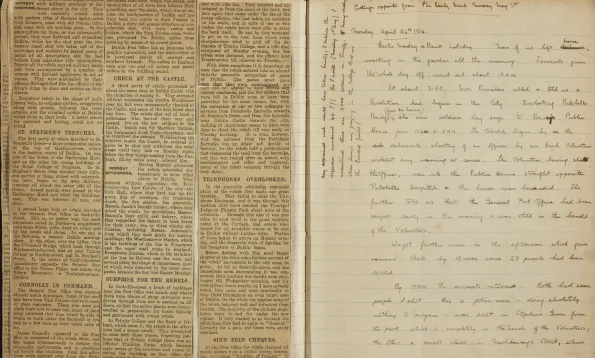

Over the next 98 pages (some blank), Herbert wrote about what he saw, both up close and at a distance; what he heard, both with his own ears and from others; and what he found interesting in newspapers, both articles and photographs, many of which he pasted onto the notebook’s pages.

The resulting document is a fascinating account of not just that momentous week, but some days and weeks after the surrender, by someone who, we’re in no doubt, wasn’t a voluntary participant. In my 25-plus years of researching the Easter Rising, I’ve read a lot of diaries and epistolary accounts of the rebellion, and I’ve also edited and published a collection of them.* But before I’d even finished reading it, I knew that Herbert G Fitzgerald’s diary is one of the better ones (and not just because the handwriting is very pleasantly legible!).

Of course, some of its descriptions can be found in other diaries, and some of the rumours he transcribes will be familiar. But Herbert has a good eye for news and for history, he’s observant and awake to the implications of what he’s witnessing, and what he’s hearing. He doesn’t accept every rumour unquestioningly, and he has no problem letting newspaper clippings tell the story where he himself has little, or no, information to add to them. He also, where necessary, doesn’t hesitate to make a drawing, where he feels his words aren’t explaining things sufficiently – including a sketch of a tram standard with ‘a shell hole punched thro’ it’ and a map of a military engagement at a Lansdowne Road junction.

Because Herbert began his account on Tuesday, the day after the Rising began, his description of the rebellion’s first day begins fairly innocuously, but quickly gets straight down to business. As that day was a bank holiday, we learn that ‘Servants [were] given the whole day off’, but in the very next sentence, ‘Mrs Ranalow called & told us a Revolution had begun’. Soldiers had laid siege to Davy’s pub nearby, and both the returning servants told of seeing people being shot on the streets. We never learn the servants’ names, but both were in a ‘very incoherent state’.

Within a remarkably short time, Herbert had learned an impressive number of facts about the Rising’s first day, with the obligatory amount of rumour thrown in, of course, including false tales of the Magazine Fort being besieged and the Volunteers using machine guns.

On Tuesday, Herbert’s reporting begins to be more immediate, and he writes: ‘Was awakened about 5 a.m. with heavy rifle fire & machine gun fire which continued for some 30 mins, should say it was about a mile away’. This is followed immediately by a reminder of just how little the seriousness of the situation had sunk in – something Herbert had in common with many eyewitnesses, and which in all likelihood led to many civilian casualties. He writes: ‘I had to try to make Trinity by 9 am as lectures are to start to-day’.

In a stunningly matter-of-fact way, Herbert describes his bicycle journey to Trinity College Dublin (TCD), encountering along the way, soldiers with fixed bayonets, scared-looking civilians, a nearby machine gun going ‘yap yap yap’, Volunteers firing from rooftops, and many barricades of abandoned motorcars. He made it all the way to TCD, but wasn’t allowed in, as the army were in possession of the campus. Cycling then to Blackrock, Herbert describes what he thinks are ‘torpedo boats and a battle cruiser’ out in Dublin Bay.

Then Herbert writes what he’s heard that day – we’re told of looting, of a Volunteer being shot by Canadians from the roof of TCD (the non-British soldiers were actually the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps [ANZACs]), and Berlin’s involvement in ‘this business’. Herbert has heard that there are as many as 7,000 rebels in the city.

By the end of the day, with ‘awful firing’ and ‘volley after volley’ going on, the fallout from rebellion is starting to hit closer to home – Herbert is writing by candlelight, because the gas supply has been cut.

On Wednesday, rumours are accumulating – ‘German Battleship sunk’; Roger Casement possibly ‘buried in College Green’; ‘the Sinn Feiners have split’ into two groups; Eoin MacNeill ‘shot by his own men’.

But life is still trying to continue as if nothing untoward was happening – TCD not only held at least one exam, but also a Parliamentary election, while bullets were ‘raining in the Front Square’.

Sleep is difficult for Herbert on Wednesday into Thursday, with ‘heavy machine gun firing between 4.30 & 5.30 am’. Nevertheless, there are more rumours to be recorded on Thursday, including a bloodcurdling tale featuring Countess Markievicz – apparently ‘a soldier was shot near the Castle’, Herbert writes, and she ‘walked up to his dead body and spat on his face’. Meanwhile, ‘Have heard that Sackville Street is piled with dead bodies’.

But again, the rebellion’s real effects – at least for Herbert living in leafy Rathmines – are more prosaic. ‘We’ve run out of coal’, he writes, ‘and none can be bought (except with a rifle)’.

By Friday, although we lucky observers know with hindsight that events were coming to an end, Herbert was having a truly terrible time, and the fear is obvious – ‘God help us for War is all over the City’. Herbert’s words underline how serious and bleak and frightening the rebellion was for ordinary citizens – and yet he was a couple of miles from the city centre. Imagine the fear of a tenement dweller living a few hundred yards from Sackville Street?

That night, the occupants of No.74 Grosvenor Road gathered in a single bedroom and looked out on a shocking sight: ‘The whole sky was red from at least two immense fires. … Volleys, machine guns, loud reports … Twice I am sure I heard screams’.

But as I say, Herbert is wonderfully observant, and in the middle of all the excitement, he stands at his window, and listens carefully to the gunfire – ‘the echoes were wonderful in the hills; several times when a solitary shot rang out in the City, I counted exactly 8 repeats in the hills’.

Things are quietening down in Dublin now, but the authorities are on an even higher level of alertness than before. Herbert’s father was challenged by a sentry to take his hands out of his pockets, and a story is told that a man who refused to do so earlier was ‘instantly shot’. Meanwhile the nature of the rumours is changing – it’s said that ‘the streets are thick with dead’ and ambulances are seen speeding along the streets.

Chief Secretary Augustine Birrell has returned from London, and Herbert (no fan of Birrell’s) writes disgustedly: ‘The blood of every person killed in this Rebellion is on his head’. Bitterly he adds: ‘this day [last] week it was honourable to be Irish, now … we are all suspects or rebels, [and] our City … is looted or burning, & as I write, a machine gun is mowing down young men who a week ago were serving behind counters & delivering our parcels’.

On Saturday, Herbert’s mood is improving, fed by tales of ‘Guinness lorries piled with ammunition, and soldiers pouring into the City’. And in a delightful reminder of how language can change radically, he tells us that he ‘made love to Mrs Rooney the newsagent & procured a Weekly Westminster & a Daily Mail’.

Tragedy puts a halt to Herbert’s mood later, when he writes that while passing the nearby house of Francis Sheehy Skeffington, he sees six-year-old Owen ‘romping about on the front grass’, oblivious to the fact that his father had been murdered in Portobello Barracks two days previously. Herbert also saw Hanna Sheehy Skeffington ‘looking awful’ and reported that ‘The boy … has been told his father is in the country, poor little kid’.

Unofficial reports that the rebellion is over are welcomed then, but the gunfire and explosions haven’t been fully silenced. And also, the privations visited upon the non-combatant population haven’t eased yet … . Herbert’s journal notes for Saturday end with ‘af’, which, he explains in the next day’s entry, was supposed to be ‘affirmation’, but ‘my candle burned out’.

Sunday’s entries are mostly comprised of clippings – lots of interesting snippets, made more interesting because of Herbert’s margin notes, comments, and sarcasm, including one single-word remark: ‘Liar’.

On Monday, May 1st: ‘Things very quiet today’. Herbert tried to enter the city, but was prevented by a soldier he described as ‘a little jew boy with a vile cockney accent’, who seems to be trying to sound both wise and simple, simultaneously, ending with: ‘I wish to Gawd I knew why I was ’ere’.

Tuesday brings ‘Peace at last!’ and although citizens still can’t cross O’Connell Bridge, Herbert is happy that at least ‘We secured a bag of coal today’.

On Wednesday May 3rd, Herbert procured a permanent official pass, allowing him to go in and out of town. And as more proof of his awareness that he’s writing in, and about, a historic time, he notes: ‘I here leave a space in which to paste the pass when of no further use’. Which dutifully he does, and it’s there for all to see, over a hundred years after he carried it in his pocket, producing it to the authorities whenever called upon to do so.

Eventually, Herbert visits Sackville/O’Connell Street and is so taken aback by what he sees that instead of describing the ruins, he pastes newspaper photos into his journal.

His pass also allows him to finally get into Trinity, which is now full of hundreds of soldiers and horses – ‘There is only one word for it: astounding’.

During a later visit to Trinity, more than a week after the surrender, Herbert writes that there were still a lot of soldiers on campus, and that he saw one of the famous improvised armoured personnel carriers which were designed and assembled in a hurry as a means of providing protection to raiding parties of soldiers. Close-up accounts of these vehicles are rare enough, but although his description is short, Herbert gives us a fascinating pen picture: ‘was looking at one of the “armoured” cars which was drawn up in front of the Dining Hall. It is a Guinness motor-lorry with an engine boiler mounted on it & the cab protected with steel plating. One well-directed shot pierced the steel plate over the bonnet, but was too spent to damage the radiator. Some wit had inscribed in purple upon the front of the car “Ye fearsome death-dealing Monster”’.

This is the type of detail that makes Herbert’s diary stand out – many other diarists have mentioned seeing one of these armoured cars, but none that I know of took the time to record a particular bullet hole, or the revealing graffiti written on the side.

Interestingly, despite some even-handed ‘reporting’, Herbert’s views on the Rising, and those involved, is clear throughout, and never more so than when he learns that the executions have begun: ‘When in town [on Wednesday 3 May] I got an evening paper – saw with joy that the leaders in the revolt have been shot’.

And whatever modern readers may think about the leaders and their fates, in his notes on the next day, Herbert shows a distinctly cold side – a pasted-in clipping describes a rebel shooting on soldiers from within ‘a blind institution’. The account finishes with ‘The troops riddled the place with bullets, and I am afraid many of the poor unfortunate inmates must have perished’. True story or not, Herbert’s handwritten note alongside says simply, and jarringly: ‘BOO HOO’.

More pasted-in clippings tell the stories of a soldier trapped in Henry Street, who has ‘lost his reason’, and the after-hours purchase of a wedding ring by Grace Gifford on the way to marry her doomed fiancé – Herbert describes both stories as impressive in their tragedy’.

So, with the increasing number of pasted clippings, Herbert’s diary is coming to a close. And it has an entirely appropriate ending – one which encapsulates everything about normality returning, life slowing to its usual pace, and events in the past being truly in the past.

Under the heading ‘Wednesday 10th May, Herbert writes: ‘Nothing to note’.

Endnotes

* Mick O'Farrell, 1916 What the People Saw (Cork: Mercier Press, 2013).

Apart from being grateful to Herbert himself for recording his thoughts and the events of Easter 1916, we should also thank Elizabeth Moore, who allowed the diary to be scanned, and of course the Digital Repository of Ireland, who carried out the scanning and have made Herbert’s account available for posterity.

Images of every page of Herbert’s Easter Rising diary can be found here: https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.p8418p10j-57

A transcription of the content can be found here (but do try and read the original!): https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.jh34hg80v-4

This review was written by Mick O’Farrell, author of four books on the 1916 Easter Rising. His collection of published works on, or relating to, the rebellion contains over 1,200 items, but, like any (proper) collection, it’s by no means complete.

Mick can be found talking about 1916 on Twitter: @MOF1916.

Image: Page from Herbert Fitzgerald. (2016) Diary of Herbert Fitzgerald, Digital Repository of Ireland [Distributor], Digital Repository of Ireland [Depositing Institution], https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.p8418p10j-57