In this blog, DRI 2020 Early Career Research Award Winner, Dr Siobhán Doyle, discusses her experiences using the visual collections in the DRI repository in her research on representations of heroic death and martyrdom in museum exhibitions commemorating the 1916 Rising.

By Dr Siobhán Doyle, Winner of the DRI Early Career Research Award 2020

The following blogpost discusses research undertaken as part of a PhD in Museum Studies at Technological University Dublin (TU Dublin) which was completed in May 2020. The research was supervised by Dr Niamh Ann Kelly and Dr Tim Stott was fully funded by the 2016 Dean of the College of Arts and Tourism Award. The research examines how representations of heroic death and martyrdom emerge in exhibitions commemorating the 1916 Rising at the National Museum of Ireland, National Gallery of Ireland (Dublin) and the Ulster Museum (Belfast) in 2016. This involved close visual analysis of artefacts and consultation of archive documents and publications from the individuals and organisations associated with them, which was partly made possible by the collections in the Digital Repository of Ireland (DRI) repository.

Examining visual materials can be challenging for researchers as they face restraints such as accessing collections, funding and institutional policies. Many of these challenges have been exacerbated by the present COVID-related restrictions. As I recently completed a PhD based on an analysis of visual materials within the context of Irish museums, this is an appropriate moment to reflect on those challenges and advocate for changes to be made to support researchers who use visual material.

In the context of my research, visual culture is a term that I use extensively and it concerns ‘visual events that privilege the viewer’ (Mirzoeff, 1998). An intentionally broad and inclusive term, visual culture addresses the predominance of visual forms of media, communication and information, and places emphasis on how this takes place ‘in a particular social context that mediates its impact’, such as a museum (Rose, 2008). Material culture is another ‘generously inclusive’ term I use throughout my research, in that it implies any made item, especially those in three-dimensional form (Jordanova, 2012). The case study exhibitions I analyse comprise artefacts of various media and provenance, ranging from everyday artefacts such as clothing and personal possessions to largescale commissioned artworks. Many of the artefacts I examine are in the DRI’s online collection, which are categorised in a way that connects artefacts, images and documents of different media, condition, material and size from different collections into thematic digital collections. In providing a platform for accessing these institutional collections remotely, the DRI is not only extending the boundaries of research to go beyond the walls of the holding institutions and archives themselves, but they are also expanding knowledge of collections through collaboration. Broadening research and sharing resources, expertise and connections from various institutions is crucial in developing a richer knowledge of visual and material culture.

The shape of my research was influenced by Ludmilla Jordanova’s The Look of the Past: Visual and Material Evidence in Historical Practice (2012) and subsequently influenced the overall structure of my PhD thesis. The Look of the Past is about the ways historians talk and write about things, as well as about how the past was experienced visually and is transmitted to us through the sense of sight. Jordanova begins with careful looking and moves on to description, analysis, contextualisation and comparison, which is a process that I followed in my examination of death-related artefacts in exhibitions in the National Museum of Ireland, National Gallery of Ireland and Ulster Museum. The sections in my thesis which carefully examine three artefacts from each of the case study exhibitions can be taken as self-contained mini case studies in the same way that my article ‘Historical Narratives on Display: The Bullet in the Brick, National Museum of Ireland’ published by the DRI is a distinct, accessible argument on the importance of extending research boundaries beyond an artefact’s holding institution, to allow new interpretations of the past to emerge (https://repository.dri.ie/catalog/vt15d640k).

(Bullet embedded in brick, https://repository.dri.ie/catalog/st74cq49d)

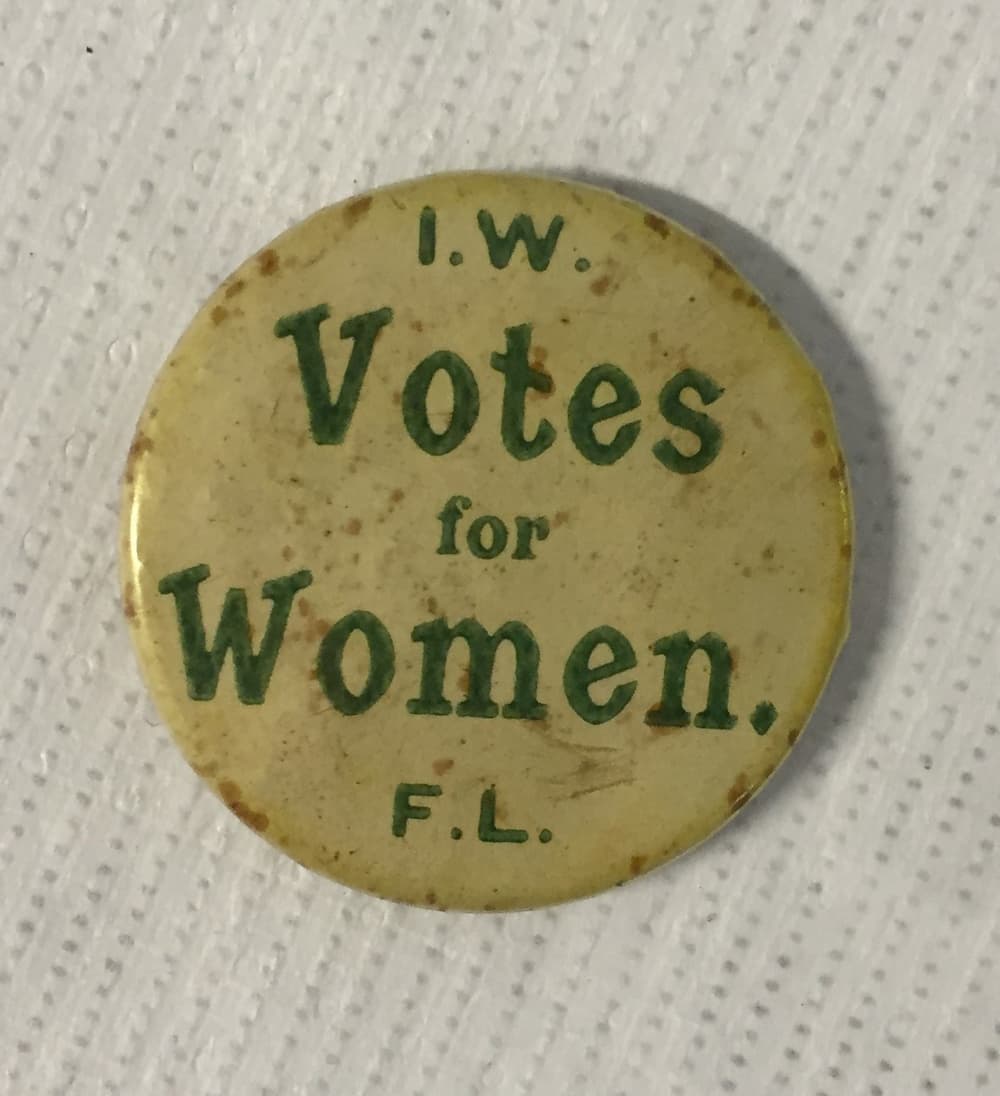

It is important to bear in mind that even when viewing artefacts, whether through the display case in an exhibition, physically handling them in an archive or viewing images online, their readable dimensions may or may not be visible (Davis, 2011). What I mean by this is that the study must also go beyond the artefact’s apparent composition so that its wider context can be examined. Take Francis Sheehy Skeffington’s Vote for Women badge in the National Museum of Ireland for example (https://repository.dri.ie/catalog/mp48sc827). Looking at the badge in association with Sheehy Skeffington, viewers become aware of his commitment to the feminist cause. Delving deeper into the story of the object, however, uncovers the badge as being pinned to the coat that he wore when he was executed during the 1916 Rising and his widow Hanna’s plight to retrieve his personal belongings after weeks of ‘persistent application’ (https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.r494vm07g). By interrogating the wider context of artefacts and the interplay between source types, we can construct deeper, more informed interpretations of historical events.

(Badge, ‘Votes for Women’, https://repository.dri.ie/catalog/mp48sc827)

(Property loss statement, https://repository.dri.ie/catalog/r494vm07g)

In a public discussion at the Royal Irish Academy Future Museums workshop in November 2019, it was noted how curated collections of value are at the heart of museums and play a role in helping society understand and reflect on difficult episodes from Irish national history (https://www.ria.ie/sites/default/files/museums_for_the_future-final.pdf). Findings from my doctoral research disclose that museum collections are under-researched, which leads to a mismatch between the artefacts and knowledge of the artefacts and how they are presented in exhibitions. In order to understand collections and indeed to understand the past, deeper engagement with the history of artefacts is required. Through my rigorous examination of the circumstances of the production, collection and display history of selected artefacts associated with death, which the work of the DRI partially facilitated, a more detailed knowledge about the artefacts has been uncovered.

So what can be done to develop deeper engagement with visual material and institutional collections? Firstly, researchers must be offered more opportunities to engage with visual material, by releasing information and generating knowledge and increasing virtual access to collections. As well as capturing and communicating information related to collections, institutions must ensure that their knowledge is regularly updated. Research is an essential part of their role, which can be carried out internally through curatorial research as part of the development of exhibitions and initiatives. External research conducted by historians, researchers and organisations independent from cultural institutions can also advance the future care, interpretation, display and public engagement with visual material. The intellectual climate in which institutions operate is constantly developing and they must ensure that their collections are always open to reappraisal. Enhancing the research culture in institutions requires a hybrid solution. It is a remit of cultural institutions to promote their collections to potential researchers, establish stronger links with the higher education sector and extend research opportunities to the public in a range of ways, from disseminating more information about the potential of their collections to providing space for visitors to work. Developing research into existing collections has as much potential to expand the possibilities of visual material as adding new items to collections. External approaches to research can invigorate collections, and cultural institutions have a responsibility to be open to all alternative perspectives.

Cultural institutions need to actively transform the content and use of their collections in order to present broader narratives and reach a diverse audience. This is a difficult process which involves considerable resources and financial investment but expanding collections is a prerequisite for an institution’s ability to present multifaceted narratives of the past. In addition to adding artefacts to their collections through purchases or donations, institutions must take steps to ensure that more of their existing visual material is used through open storage, touring exhibitions and sustained loan schemes. It is also the responsibility of cultural institutions to expand their archives by consulting and collaborating with other available resources such as the DRI. The combined consultation of various archive and institutional resources in my PhD research demonstrates the value of expanding research parameters and going beyond the archives of the particular institution under analysis. The present global pandemic which we are all negotiating offers an opportunity for substantial change in the way cultural institutions think about visual material. Supporting more digitisation of collections such as the NMI’s Historical Collections Online and adding value to existing digital resources such as the DRI allows for remote access to visual material and, crucially, to a wealth of information about them.

References

Davis, Whitney. A General Theory of Visual Culture. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Digital Repository of Ireland. Hanna Sheehy Skeffington. (2016) Property loss statement, Digital Repository of Ireland [Distributor], National Museum of Ireland [Depositing Institution], https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.r494vm07g.

Digital Repository of Ireland. Irish Women’s Franchise League. (2015) Badge, ‘Votes for Women’, Digital Repository of Ireland [Distributor], National Museum of Ireland [Depositing Institution], https://repository.dri.ie/catalog/mp48sc827.

Jordanova, Ludmilla. The Look of the Past: Visual and Material Evidence in Historical Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Mirzoeff Nicholas, ed., The Visual Culture Reader. London/New York: Routledge, 1998.

Rose, Gillian. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials (Second Edition). London: Sage, 2008.

Royal Irish Academy, “Museums for the Future: Policies and Practices in Ireland.” https://www.ria.ie/sites/default/files/museums_for_the_future-final.pdf.